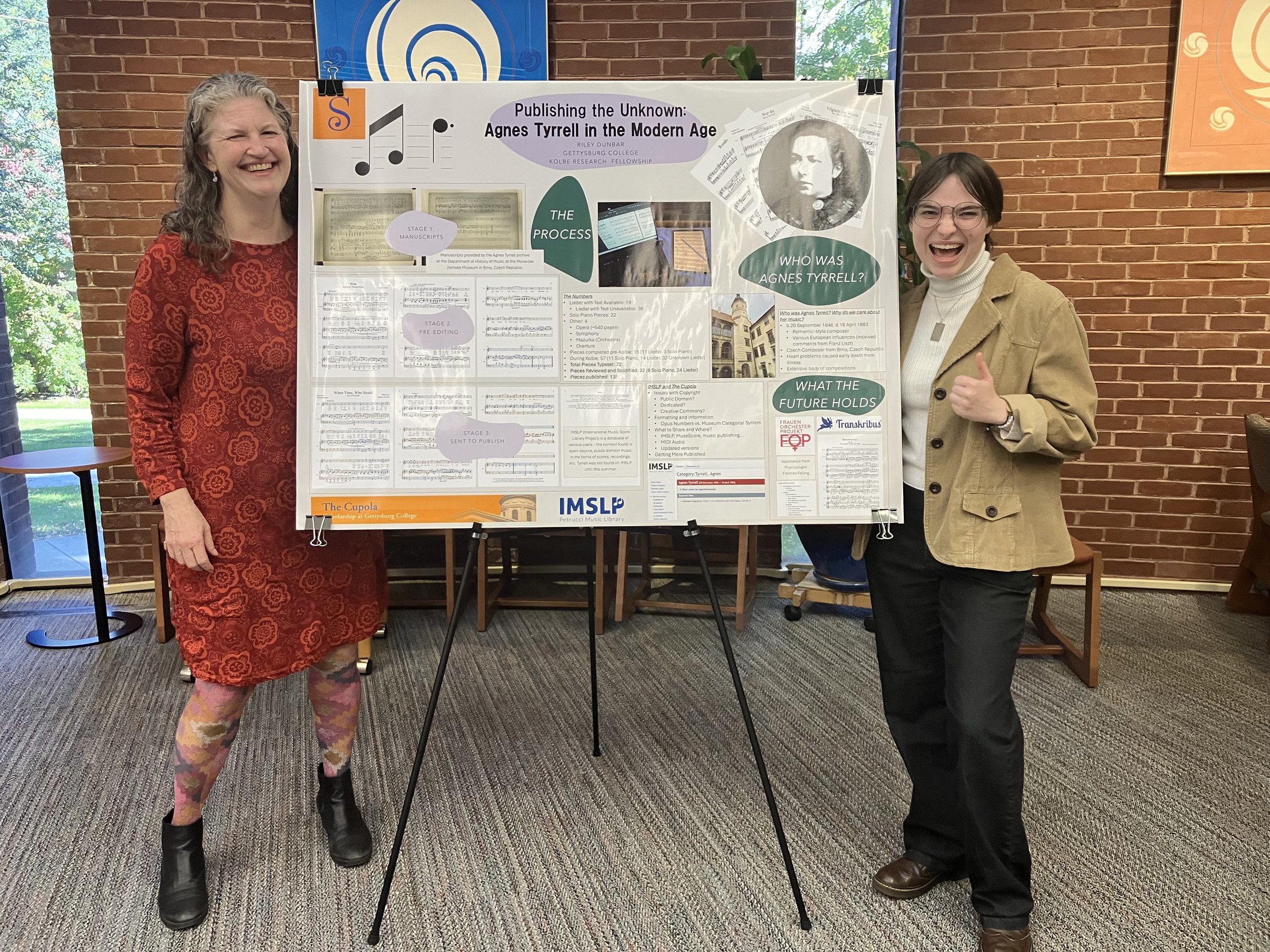

Last week Riley, my wonderful research assistant, did a poster presentation along with the other Kolbe fellows who spent the summer doing research here at Gettysburg College. It was so fun running into people who had visited Riley’s poster and were excited about Agnes and the overture performance in March. I kept hearing “So you’re going to Berlin? Can I come?”

I also had a nice conversation with one of my chamber music students, Micah. He’s a double major and a beautiful violist; I’m coaching him on the Brahms E flat sonata. I love seeing our students thrive in different areas. His project was going on a Maya archeology dig, using LIDAR technology to find structures under the ground. LIDAR stands for Light Detection And Ranging, and it makes it possible to look from way overhead at even a jungle canopy, and see through it to the structures underneath the ground. So Micah and his cohort found spots and dug them up to reveal a canal and a terrace, proof of civilization that the surface of the ground doesn’t reveal. I learned my new favorite word: ground-truthing. The technology makes it possible to find the truth under the ground. And that’s so similar to what’s happening with Agnes. The manuscripts were lovingly catalogued and cared for through the 20th century, but it just didn’t make sense for anyone to painstakingly copy out every note before being able to find out if out if the music was worth the trouble. But now I can waltz in with my phone, and take hundreds of photographs in a day. The music was always there, but it was hidden beneath the ground. Now we’re ground-truthing it. Good, right?

I also talked to another research fellow who gratified my nerdy English major heart with a paper on time and bells in Mrs. Dalloway—too long since I’ve read it—and The Doomsday Book by Connie Willis. I read that last summer along with its cheerier sequel, To Say Nothing of the Dog, and haven’t been able to shut up about them…maybe sort of like I haven’t been able to shut up about Agnes’s music: I found a thing! It’s so well crafted and emotional and brings me so much joy, and you have to experience it too! She made me so happy by saying she’s thinking of being a high school English teacher—she’ll be absolutely incredible, and she’ll change her students’ lives. We had a nice talk about festival time, moments outside of the regular cycle when people come together to celebrate something and the focus is away from the regular routine. I said, “like this event.” It felt so good to have a moment, out of the regular Friday afternoon time, to celebrate the students and their excellent work. I want to think about making more moments like that.

So I felt like the English major and I were kindred spirits, as Anne of Green Gables says. I’m rereading AOGG, out loud to my son at bedtime, and I keep thinking about how Agnes’s world was, in some ways, like Anne’s. Of course Agnes is a city European, not a rural Canadian, but the time period is similar: Anne’s youngest daughter Rilla is a teen in WWI, so Anne is probably a child in the 1870s (ah, the internet knows. Anne was born in 1865.) Agnes lived from 1846 to 1883. So I’m revisiting fictional Avonlea, this world I know so well, but this I’m time noticing the technology. There are trains, yes, but a horse and carriage is what takes you from the station. Music is only live. And night is dark. There’s a scene where Anne stops studying because it’s twilight and she can’t really see her book anymore, so she looks out the window at her favorite tree in the darkening sky. I don’t know if Agnes had electric lights in her apartment in her sophisticated city—she might have—but she might have lived some of the time in oil light and candlelight.

And now here I am, typing on a glowing screen.

It’s good that I’m feeling grateful for technology, because I’ve also been really frustrated with it lately. Working on the overture—that is, proofreading Riley’s typeset notes from my photos of Agnes’s handwritten manuscript--uses really different intellectual muscles than the ones I use to learn piano music, or even to edit piano music. I’ll spare you the details—they’re crushingly boring—but I got into the kind of situation where software was crashing, and making me re-enter passwords a million times ,and refusing to save my work, and I had clearly angered the technology gods, and it was really hard not to have a tantrum about it. In fact, I failed, and I did have a tantrum about it. It’s so much easier to look at notes on a page and teach my fingers how to play those notes, without having a computer be involved.

Some of the challenges of editing of the overture aren’t technology’s fault, though, they’re about my own inexperience with reading orchestral scores. I’m used to reading piano music, but orchestral music is a whole different game. Some of the parts are very easy for me to read (hello, my dear violins and cellos and flutes), but some of the parts require an extra cognitive step. The harder ones are in different clefs or transposed; imagine you’re reading lots of numbers, and then a few of the numbers you have to, say, add 3 to them: so you’re reading 3,4,5 for violins and clarinets and thinking 3, 4, 5 for the violins and 6, 7, 8 for the clarinets. It’s kind of like that, and oh my brain. People get great at that with practice, but I haven’t done it much since I took a conducting course in grad school a million years ago. So there’s a lot of moments of trying to figure out what it’s supposed to sound like while stumbling and feeling confused. Agnes also occasionally makes errors with the transpositions, which makes sense: she usually wrote for piano or piano and voice, and once in a while she forgets—say, adds 3 instead of subtracting 3. It doesn’t happen very often, and it’s comforting to know that she was human, and this challenging thing was hard for her too.

And I know that we have to find all the errors—mine, Agnes’s, and Riley’s—before we make the individual parts, because every error in the score is wasting a whole orchestra’s worth of individual people’s five minutes, and that makes my blood run cold. Someone at the poster presentation event asked me how I can tell if something is an error or an artistic choice, and I said part of it is knowing the language, and trusting that knowledge. So if someone says “the violas are in the library” and “the clarinets are in the library” and “the cellos are in the park,” it’s probably an artistic choice to say “library” or “park.” But if they say “the cellos in the are library” it’s probably a mistake in the cellos.

So I’m being really detailed in a different way than I usually work, and dang is it humbling. But tantrums and perfectionism aside, it’s exciting to still be able to find new musical skills and ways of knowing. Lifelong learning, baby!