Agnes didn’t just compose music, she also wrote poetry (delighting my English major heart).

I took photos of Agnes’s poems when I was at the archive in the Czech Republic last year. That was a complicated trip: my dad was in hospice, and I was far away, ping-ponging between joy and sorrow (and also the worst case of poison ivy I’ve had in my life). I was thrilled to photograph the poems but I couldn’t read them yet: Agnes wrote in Kurrent, an old German style of handwriting that I’m not trained to read. So I hired someone to transcribe the poems, and I finally got the transcriptions in September. We live in the future, so I ran the transcriptions through two AI translation programs: Google Translate and DeepL. My anecdotal observation is that DeepL is more accurate but Google is more eloquent. I made a spreadsheet with columns for the German, both AI translations, and my own version. The last column is still in process: I’m combining the two translations with my own intermediate German to make my own best guess. That’s a new experience. I’ve never really translated poetry before, and it’s fun to think about language in that way. But there’s also something about translating poetry that feels very familiar from the process of translating music from notes on a page to sounds in a room. What’s the tone? Is this moment arch or poignant, funny or profound? Is my reading right? I also can’t help thinking about my dad, who had a PhD in comparative literature. I would have loved to talk with him about translating these poems. Dammit.

Anyway, at first glance, and indeed at dozenth glance, Agnes’s poems are very typical nineteenth-century Romanticism: lots of beautiful nature imagery, some individual searching for meaning in the universe, some death, some yearning. Something that stands out to me, though, is that most of the yearning seems directed at women: there’s some longing to “kiss her neck,” and some rosy cheeks and blue eyes, and a “firm, chaste bodice.” When I first read the AI translations, I immediately started texting some of my people: “Whoa! Agnes wrote love poems to women!!!”

Ade, Du sanfte zarte Maid,

Ich muß von hinnen wandern.

Dein bleibt dies Herz in Ewigkeit,

Ich schenk' es keiner andern.

Farewell, gentle, tender maiden,

I must wander far away.

This heart remains yours forever,

I give it to no other.

But I can’t be sure. Maybe she was imagining how someone might feel about *her*. Maybe she felt like a poet’s voice was supposed to be male. And maybe none of the poetry is in her own voice at all. In some poems she overtly takes on different voices that definitely aren’t herself, narrating as an old man and a young mother and even a chorus of drinkers.

If she is writing as herself, maybe she did love some men: there are a couple of poems lamenting a lost beloved with male pronouns.

Wie war ich doch heiter

Wie lustig, wie froh,

Mein Herz fült ich weiter

Er liebte mich so.

How cheerful I was,

How happy, how joyful,

My heart was full,

He loved me so.

But I can’t help finding it striking that she writes so, well, sexily about embracing women.

Leg's Köpfchen noch auf meine Brust,

Laß Aug' u. Mund mich küssen,

Bis ich berauscht von dieser Lust,

Von Dir werd scheiden müssen.

Lay your little head on my breast,

Let your eyes and mouth kiss me,

Until, intoxicated by this pleasure,

I must part from you.

Whether she’s writing in her own voice or not, the natural imagery is lovely: woods and flowers and rivers, and dialogues with the sun and the moon. It so happens that where I live, in Pennsylvania, the natural foliage is very similar to that in the Czech Republic; when I hike there, I keep recognizing weeds that I know from my own garden (I’m an extremely laissez faire gardener). So I like to think I can imagine the woods and landscape Agnes was describing.

Here’s a moment for autumn, enjoying all those beautiful colors even as they’re a reminder of winter and death:

Es rauscht das Laub vom Sturm bewegt,

Der pfeift die alte Weise,

Vom Lenz den er in's Grab gelegt

Und dreht sich toll im Kreise.

In buntem Wirbel gelb u. rot

Schwingt er das Laub vom Baume,

Entblättert ächzt in Todesnot

Die Eich am Waldessaume.

The leaves rustle, stirred by the storm,

Which whistles the old tune

Of spring, which it laid in the grave,

And spins madly in circles.

In a colorful swirl of yellow and red

It swings the leaves from the tree.

The oak tree at the edge of the forest,

stripped of its leaves, groans in agony.

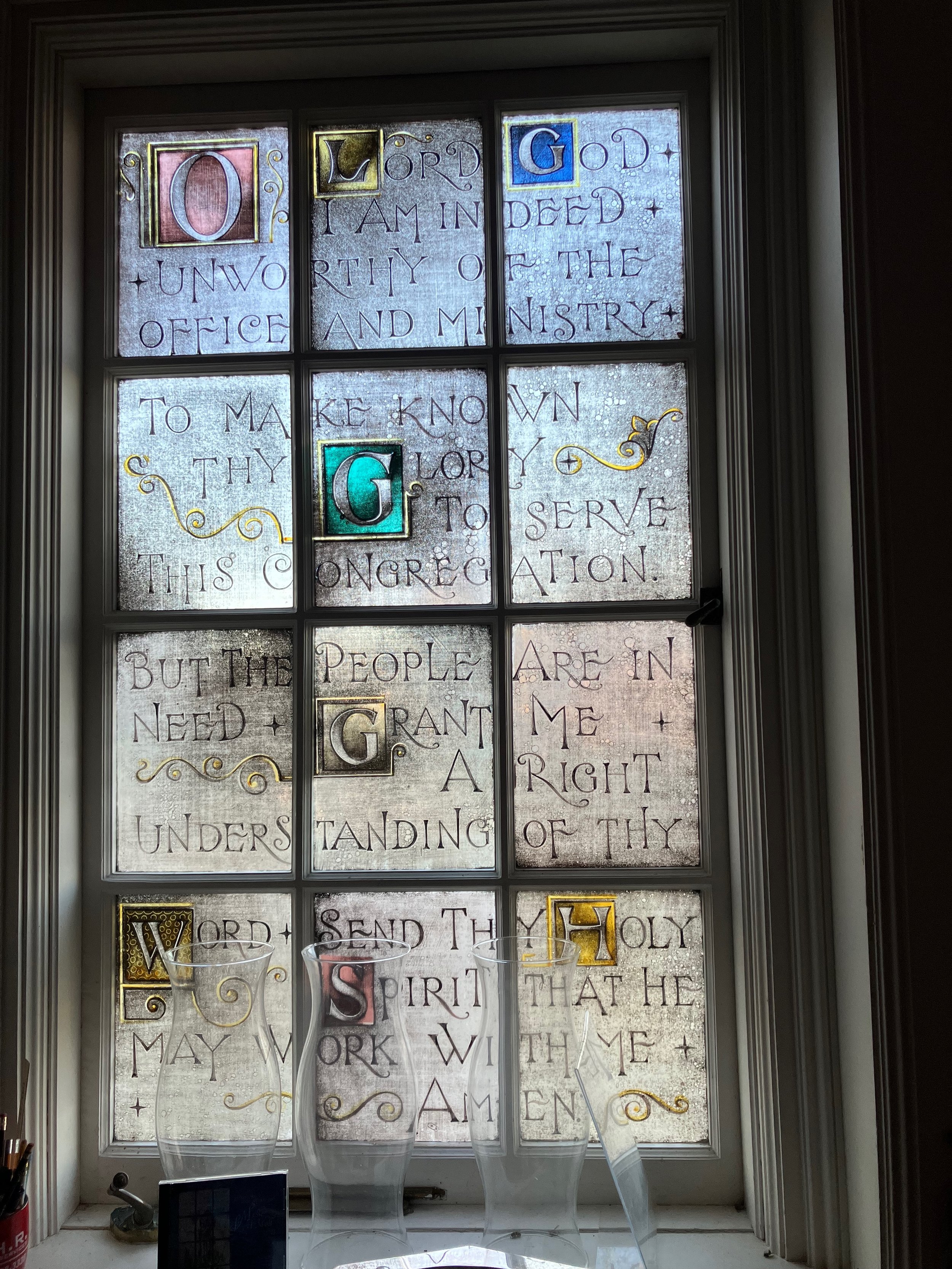

And here are the rustling leaves I can see from my office window. I love this time of year. And I love that questions, too, keep swirling around: there’s always more to be curious about.